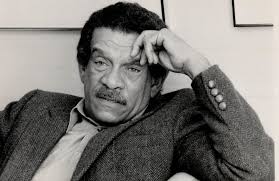

Teju Cole in Sunday Book Review, The new York Times

“Writing poetry is an unnatural act,” Elizabeth Bishop once wrote. “It takes skill to make it seem natural.” The thought is kin to the one John Keats expressed in an 1818 letter to his friend John Taylor: “If Poetry comes not as naturally as the Leaves to a tree it had better not come at all.” Bishop and Keats both evoked a double sense of “natural”: that which is concerned with nature, with landscape, flora and fauna, and that which is unforced and fluent. In both senses, Derek Walcott is a natural poet.

Walcott, who turned 84 this year, began writing young. His first poem appeared in a local paper when he was 14, and his first volume, “25 Poems,” was self-published when he was 18. “Everyone wants a prodigy to fail,” Rita Dove wrote. “It makes our mediocrity more bearable.” Walcott did not fail. His early poems were expert, and even though they bore traces of his apprenticeship to the English tradition (in particular W. H. Auden and Dylan Thomas), they were to prove thematically characteristic. Right from the beginning, he was keen to use European poetic form to testify to the Caribbean experience.

About the August of my fourteenth year

I lost my self somewhere above a valley

owned by a spinster-farmer, my dead father’s friend.

At the hill’s edge there was a scarp

with bushes and boulders stuck in its side.

Afternoon light ripened the valley,

rifling smoke climbed from small labourers’ houses,

and I dissolved into a trance.

I was seized by a pity more profound

than my young body could bear, I climbed

with the labouring smoke,

I drowned in labouring breakers of bright cloud,

then uncontrollably I began to weep,

inwardly, without tears, with a serene extinction

of all sense; I felt compelled to kneel,

I wept for nothing and for everything

Leave a Reply